The desktop SmartArt gallery in PowerPoint does not show every layout that exists. After some experimentation, I found 23 layouts that are missing from it. Some only surface through Designer suggestions, and a second group only appears in the SmartArt menu of PowerPoint for the web. In this post I catalog all of them, show what each one looks like, and include a downloadable PPTX with copy-and-paste-ready diagrams.

I discovered this by accident. While working with PowerPoint on the desktop, the Designer suggested a diagram style I had never seen in the SmartArt gallery. I went back to Insert > SmartArt to look for it. It simply was not there. That sent me down a rabbit hole of typing different bullet lists and watching what Designer would suggest.

How to access them

- Open a blank slide in PowerPoint.

- Type a short bulleted list (3 to 5 items work best).

- Open the Designer pane from the Home tab or press Design > Designer.

- Scroll through the suggestions. Some of the proposed layouts are SmartArt diagrams that you will not find in the SmartArt gallery.

Tip

Designer needs an active Microsoft 365 subscription and an internet connection to generate suggestions. Make sure both are available.

Overview

The 23 layouts split into two groups: 15 that are only reachable through Designer, and 8 that also appear in the SmartArt menu of PowerPoint for the web. None of them show up in the desktop SmartArt gallery.

List-style layouts

| Layout | Available via |

|---|---|

| Icon Label List | Designer only |

| Icon Circle List | Designer only |

| Icon Circle Label List | Designer only |

| Icon Leaf Label List | Designer only |

| Icon Label Description List | Designer only |

| Centered Icon Label Description List | Designer only |

| Icon Vertical Solid List | Designer only |

| Vertical Solid Action List | Designer only |

| Vertical Hollow Action List | Designer only |

Process and timeline layouts

| Layout | Available via |

|---|---|

| Basic Process New | Designer only |

| Basic Linear Process Numbered | Designer only |

| Linear Block Process Numbered | Designer only |

| Linear Arrow Process Numbered | Designer only |

| Vertical Down Arrow Process | Designer only |

| Chevron Block Process | Designer only |

| Repeating Bending Process New | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

Timeline layouts

| Layout | Available via |

|---|---|

| Basic Timeline | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

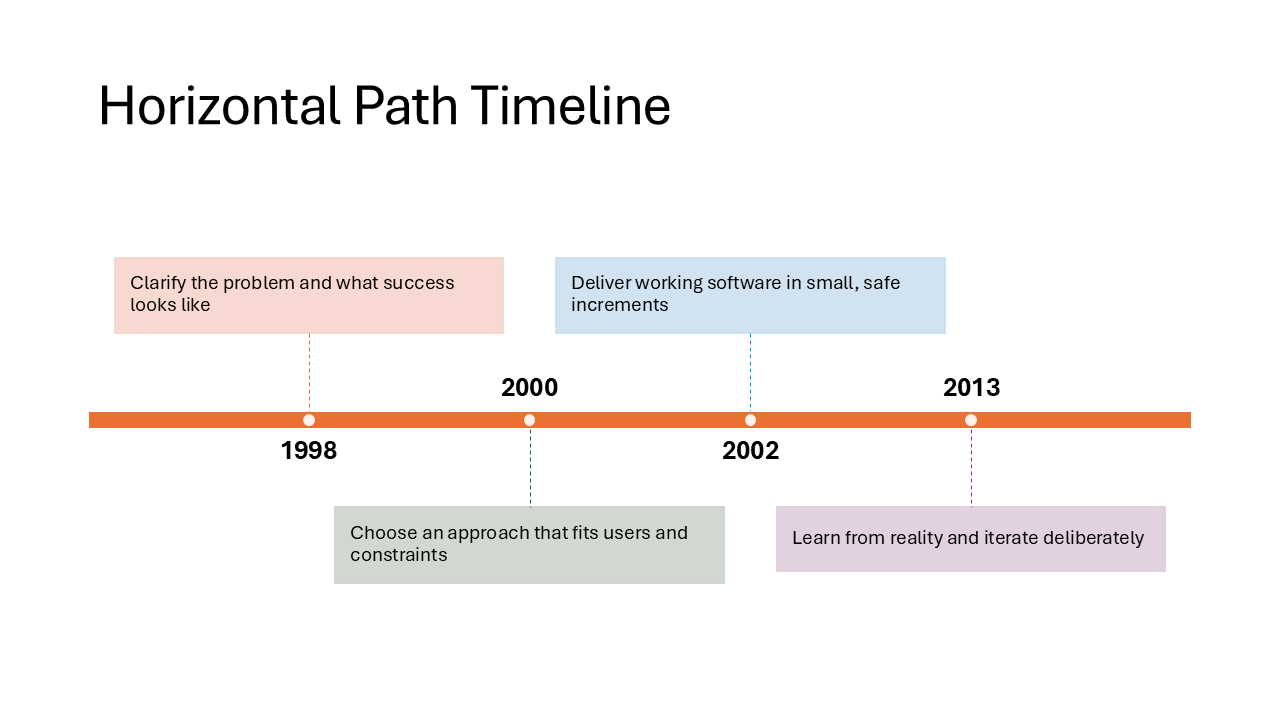

| Horizontal Path Timeline | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

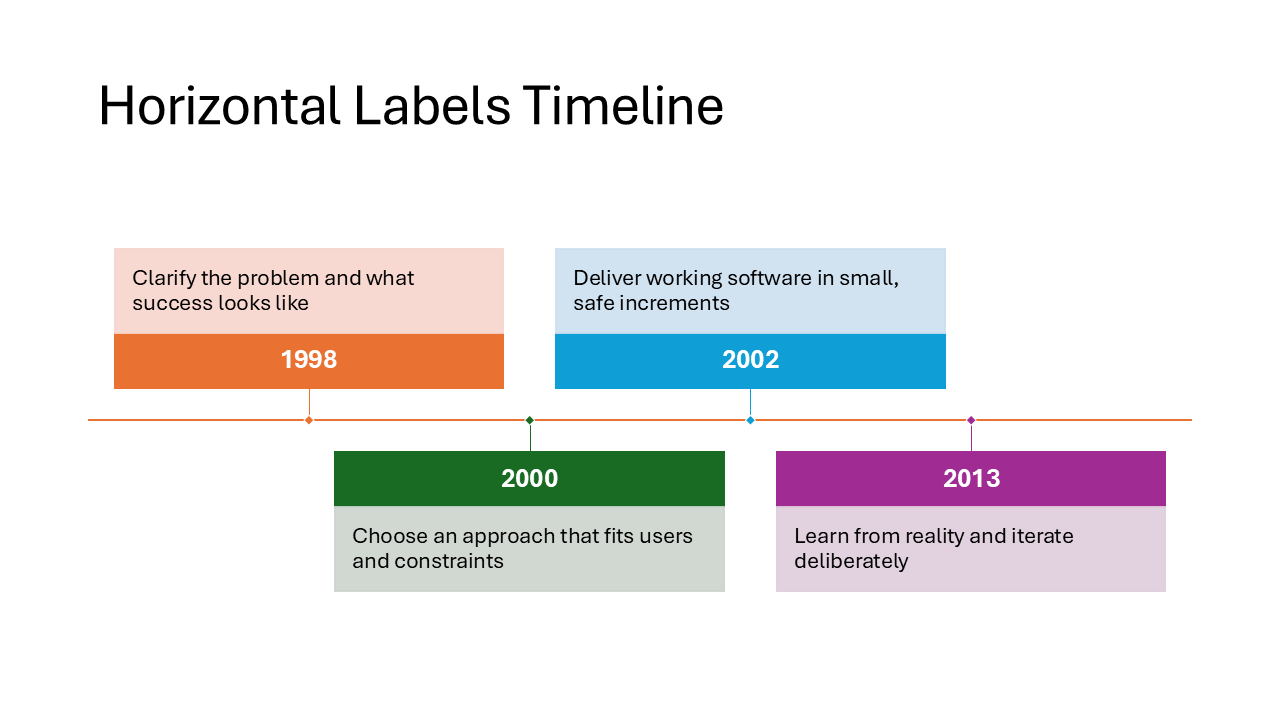

| Horizontal Labels Timeline | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

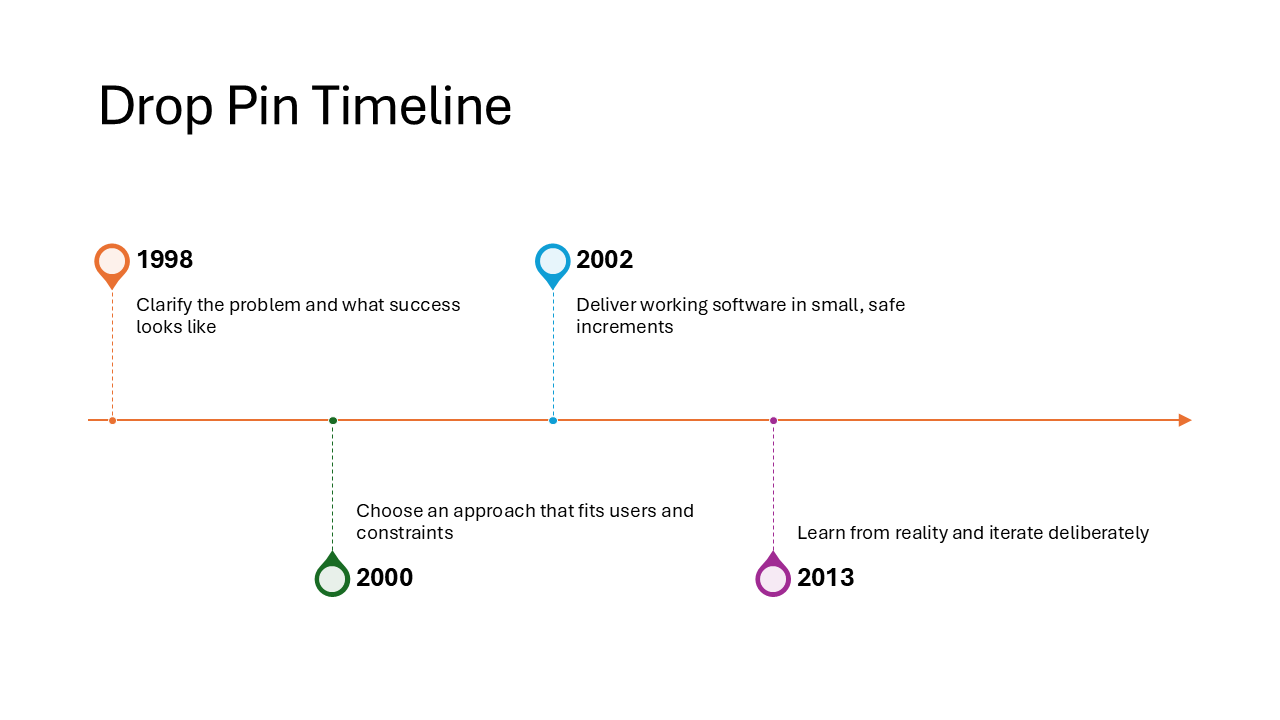

| Drop Pin Timeline | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

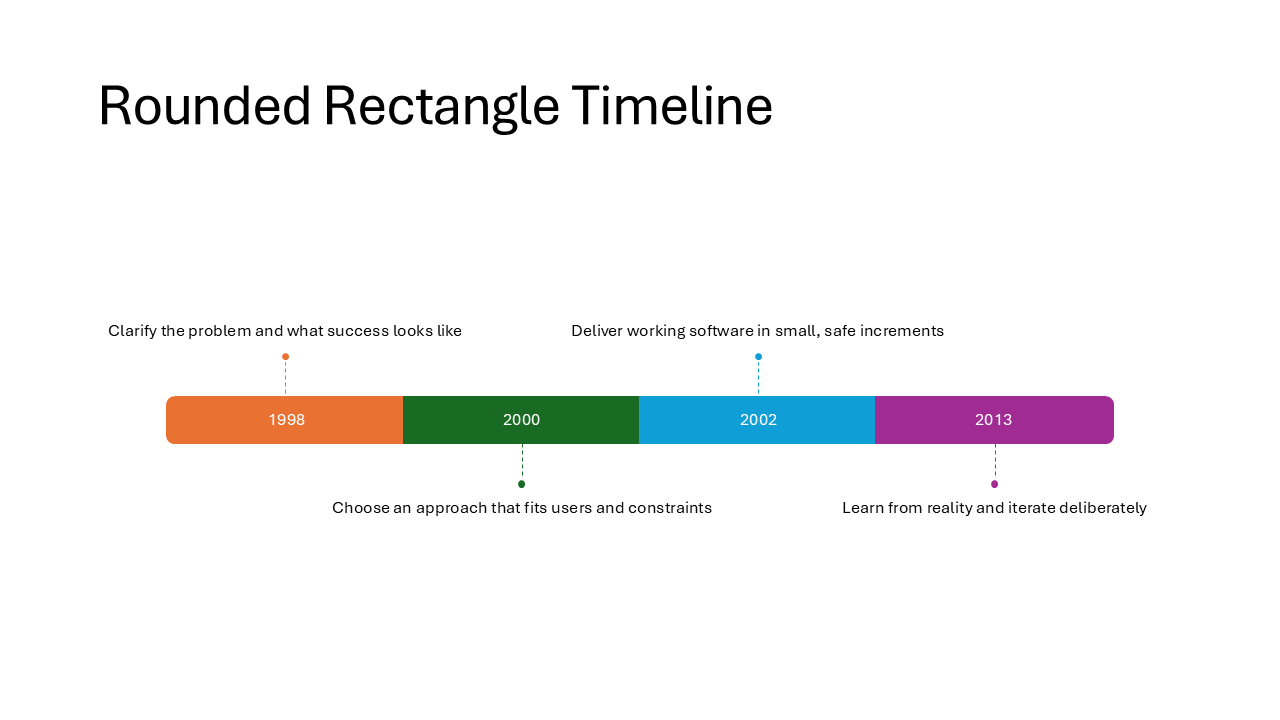

| Rounded Rectangle Timeline | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

| Hexagon Timeline | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

| Accent Home Chevron Process | Web SmartArt menu + Designer |

Designer-only layouts

These 15 layouts do not appear in any SmartArt menu. The only way to get them onto a slide is through a Designer suggestion, on both the desktop and web versions of PowerPoint.

Note

The first few layouts show up frequently in Designer, so some people may not consider them “hidden” anymore. I include them for completeness, because they still do not appear in the desktop SmartArt gallery. The remaining layouts are much more elusive: I have only seen them a handful of times.

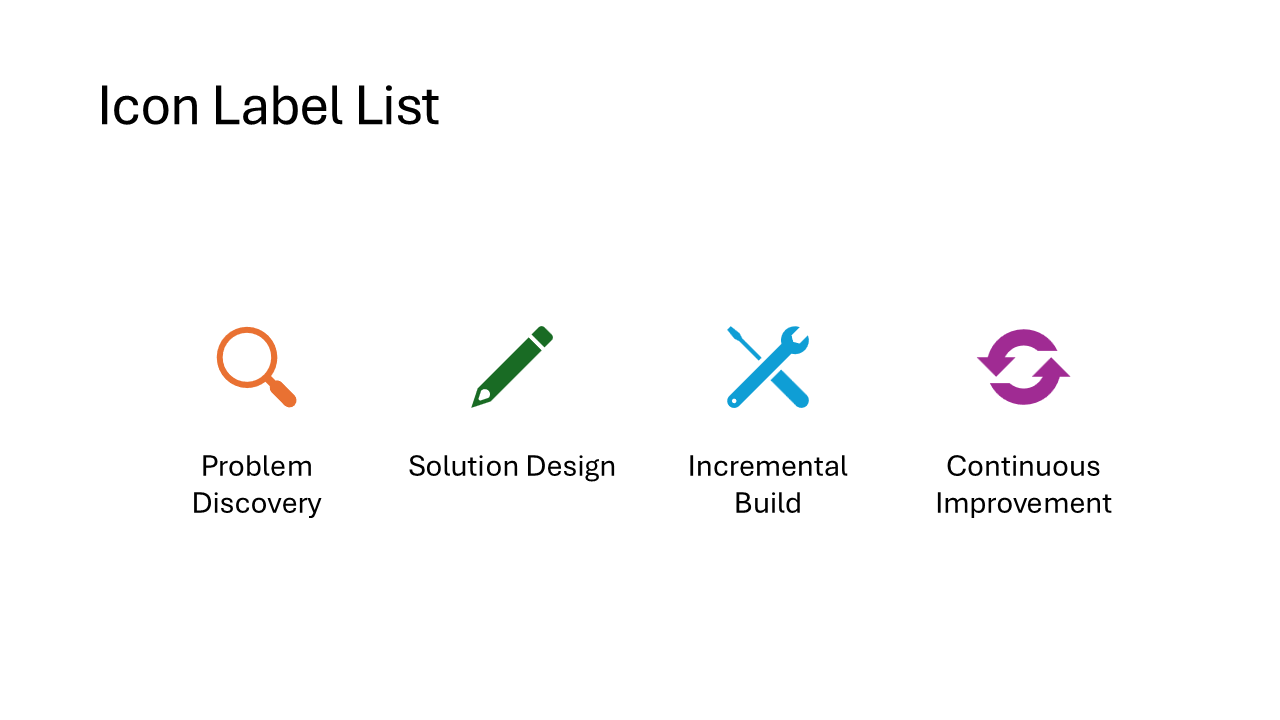

Icon Label List

Each item gets a small icon on the left with a short caption beside it. The layout arranges items horizontally, so it works best with 3 to 5 concise labels. Think feature highlights or a row of team roles.

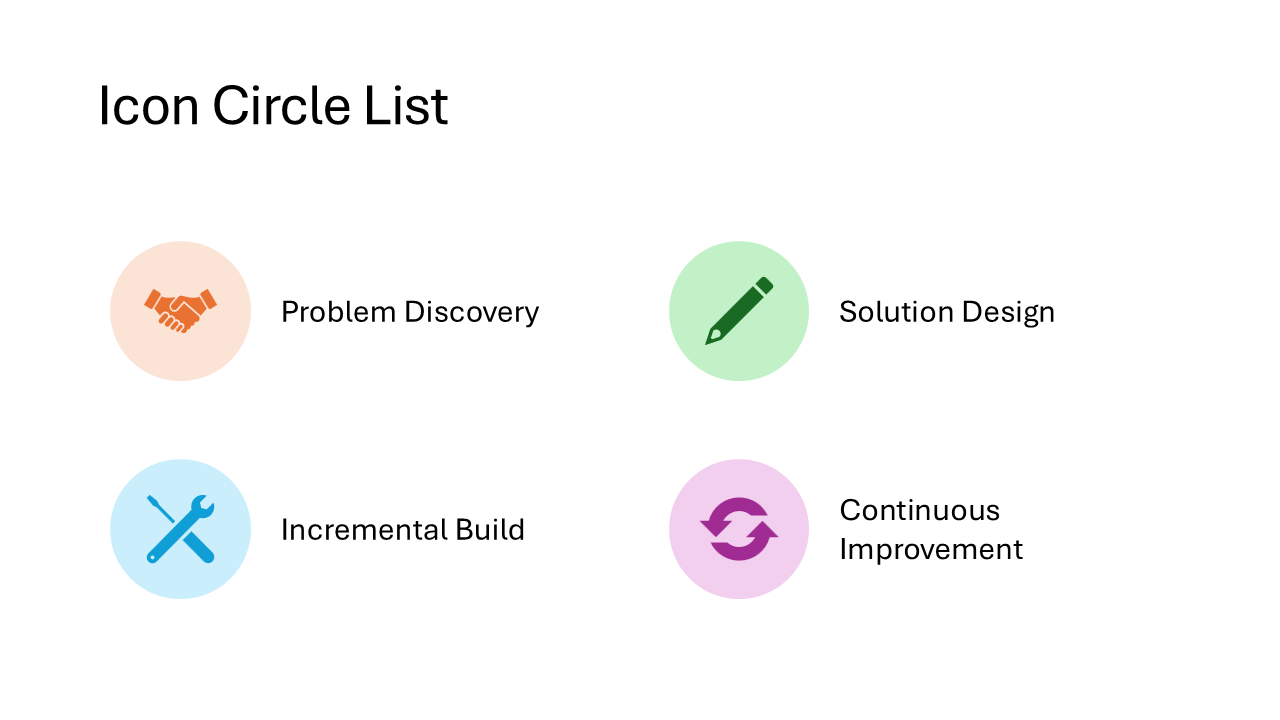

Icon Circle List

Icons sit inside colored circles with a heading and a short description underneath each one. The circles give the slide a polished, uniform look. A good pick for introducing team members, product pillars, or service categories.

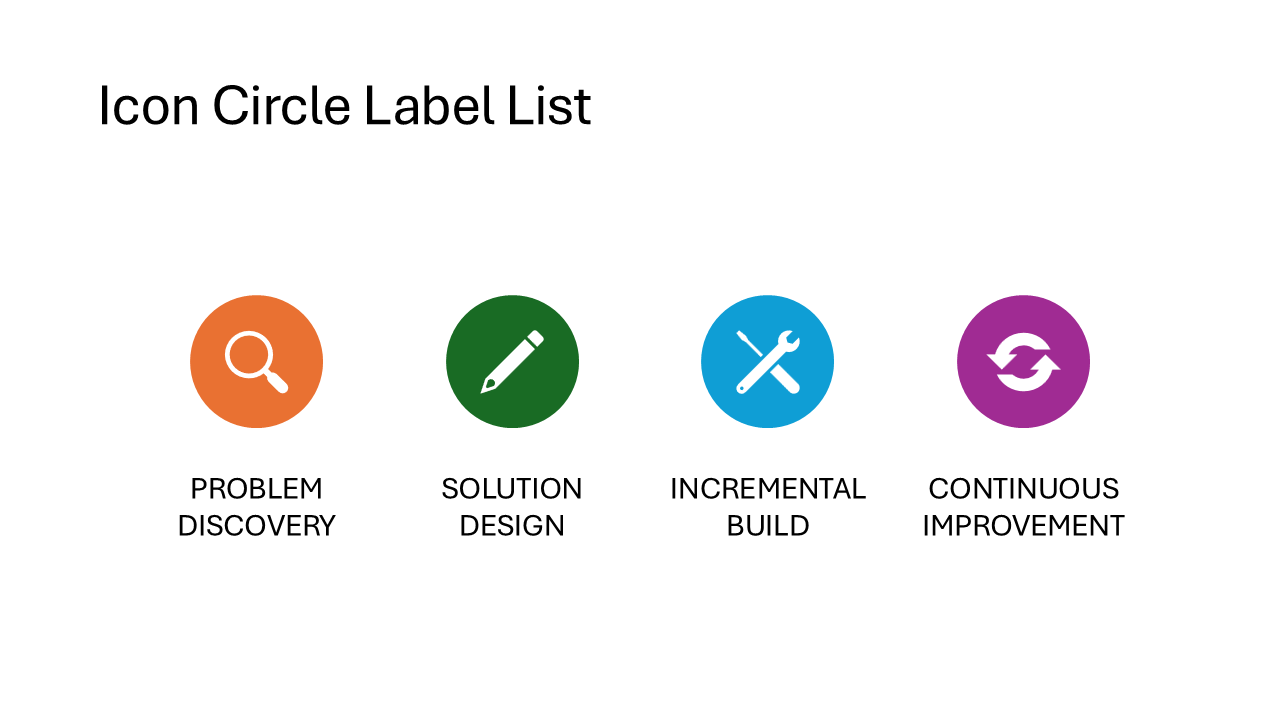

Icon Circle Label List

A variation of the Icon Circle List where the label text is the star of the show. Each circle holds an icon, but the emphasis shifts to the heading text below, with descriptions taking a back seat. Use this when the category names matter more than the details.

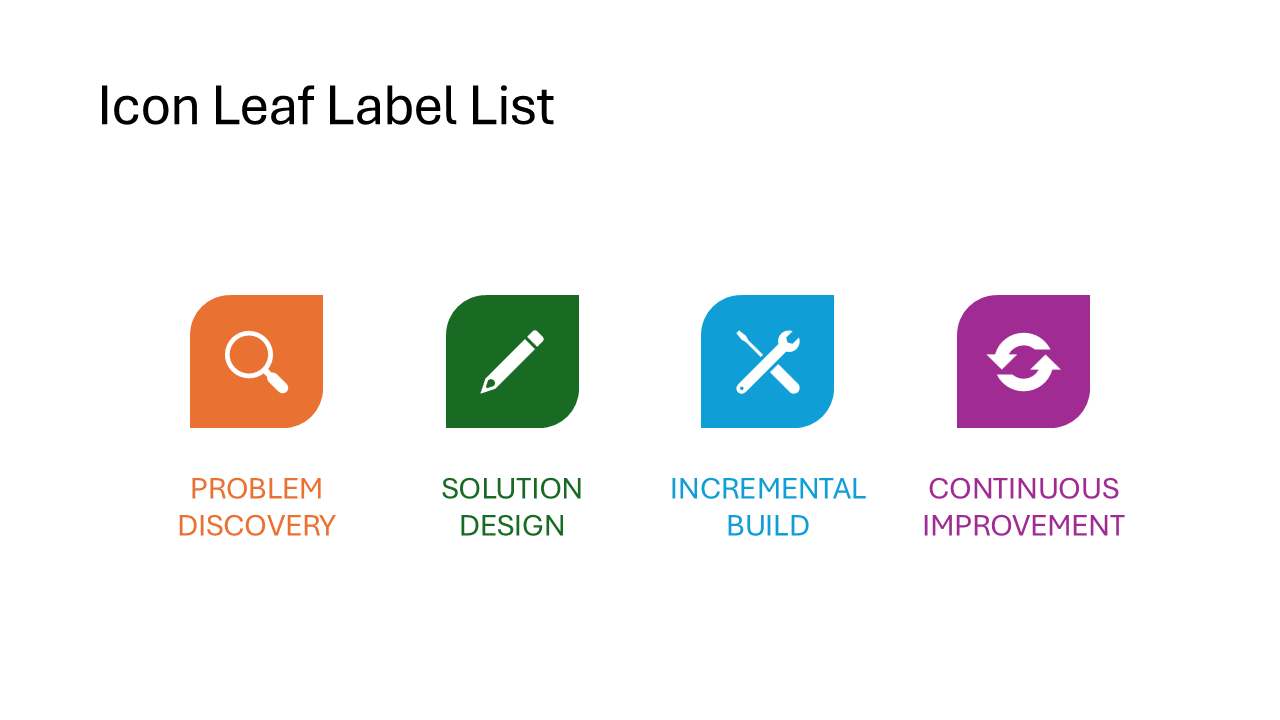

Icon Leaf Label List

Icons are placed inside leaf-shaped holders, giving the slide an organic, softer feel compared to circles or rectangles. The layout works well for topics like sustainability, growth stages, or anything that benefits from a less corporate visual style.

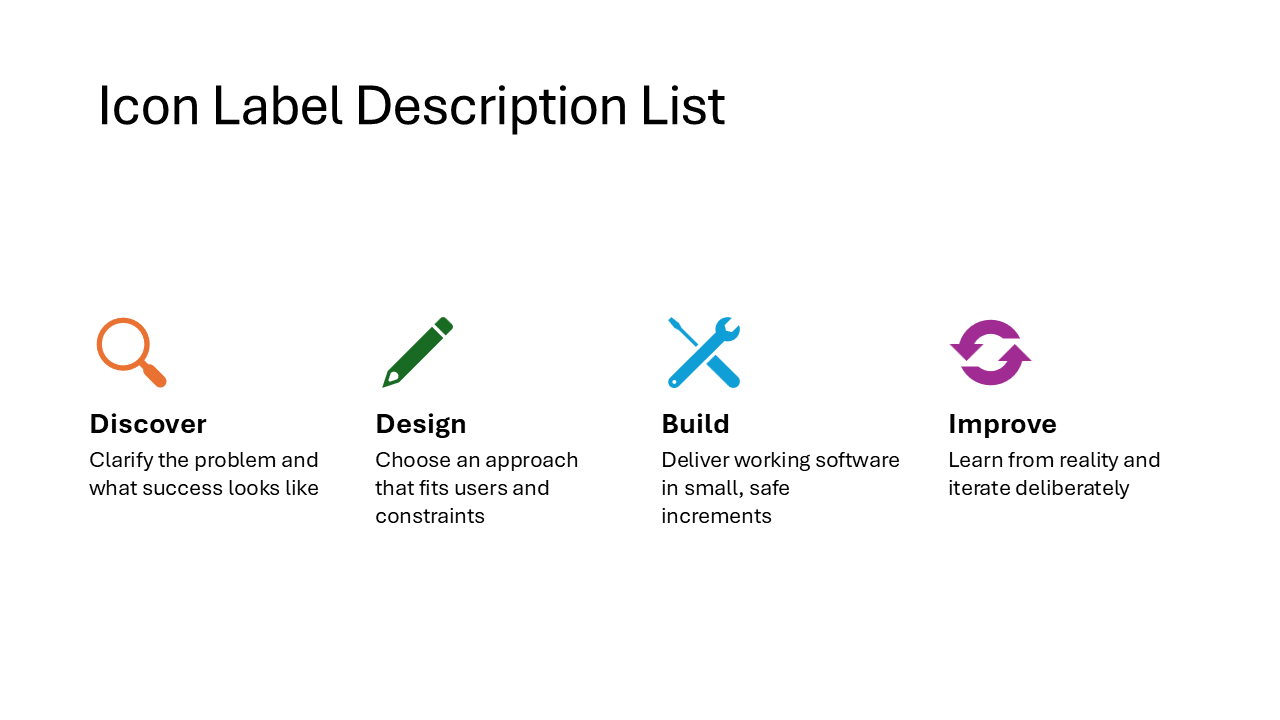

Icon Label Description List

Each item has three layers: an icon, a bold heading, and a longer description paragraph. The items are arranged horizontally and give equal space to each entry. Ideal for feature comparisons or explaining three to five concepts that each need a sentence of context.

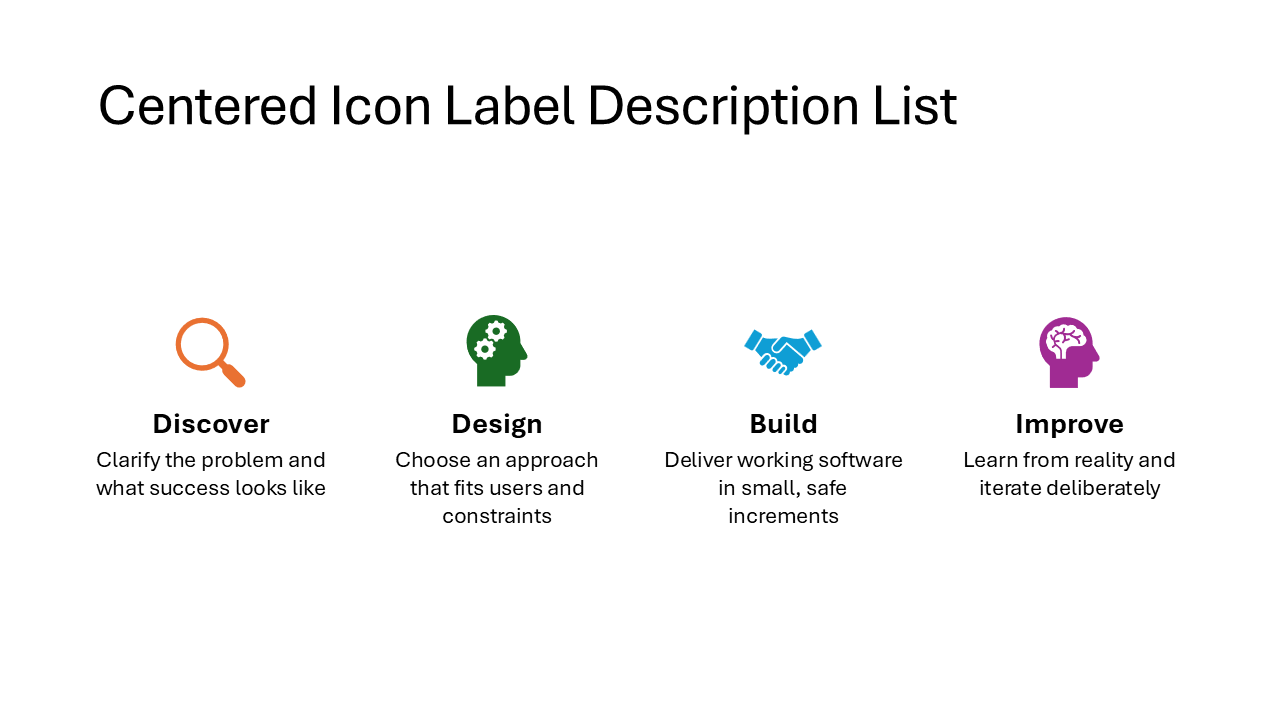

Centered Icon Label Description List

The same icon-heading-description structure as the previous layout, but everything is center-aligned. This gives the slide a more balanced, symmetrical appearance. Works well for title slides or when the content is short enough that centered text stays readable.

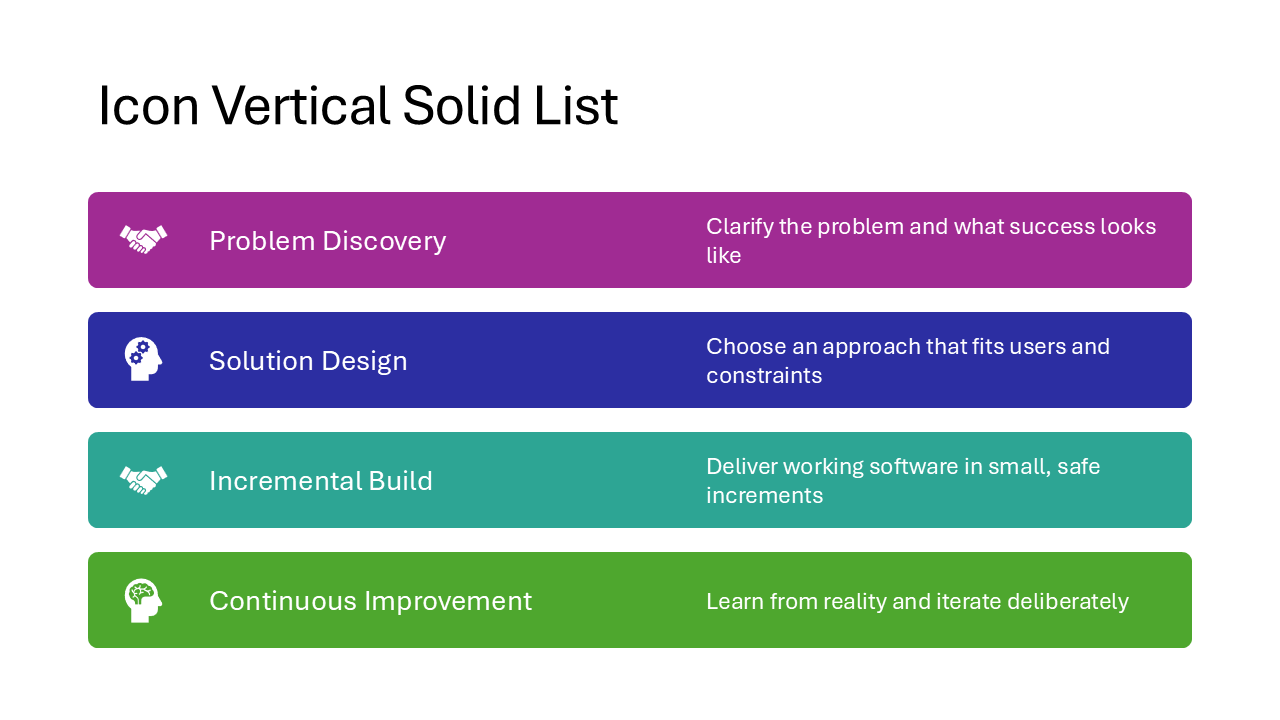

Icon Vertical Solid List

Items are stacked top to bottom, each inside a solid colored bar with an icon on the left and text on the right. The vertical orientation makes it suitable for slides with more items or longer descriptions than the horizontal variants can handle.

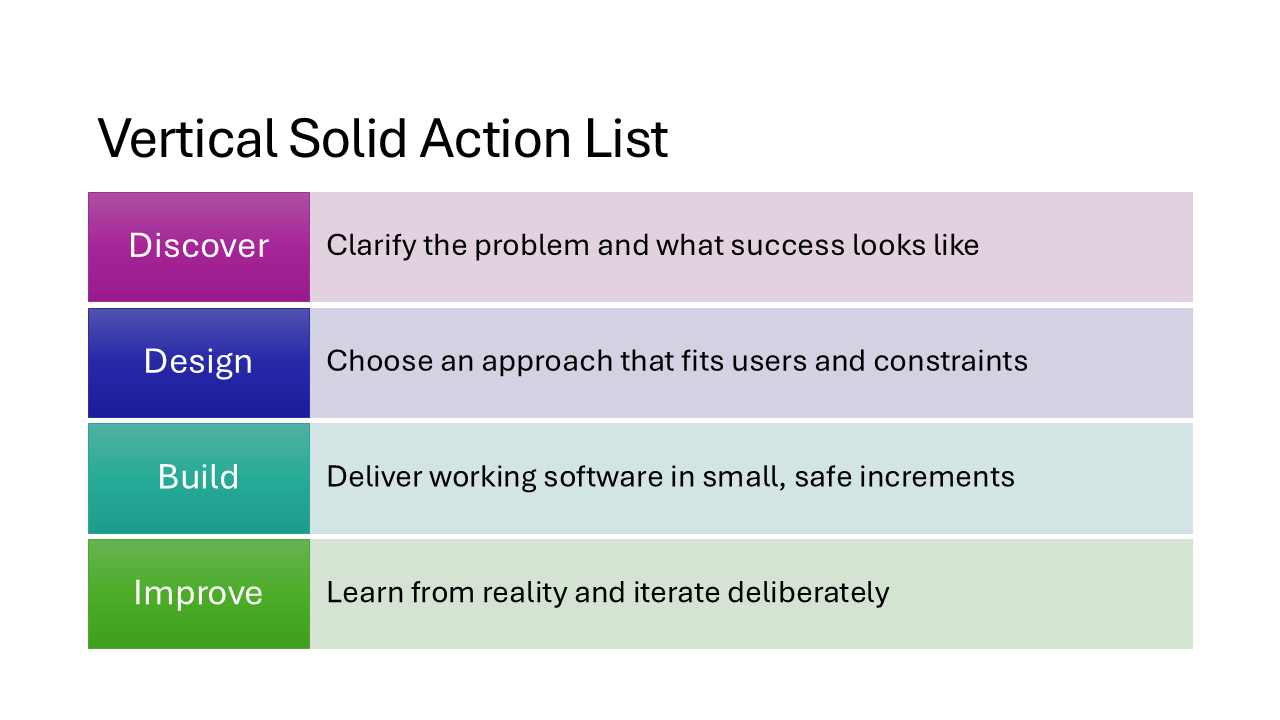

Vertical Solid Action List

Full-width solid bars stacked vertically, each holding a heading and description. No icons, no numbering, just bold blocks of color that give every item equal visual weight. A strong choice for agenda slides or listing key takeaways.

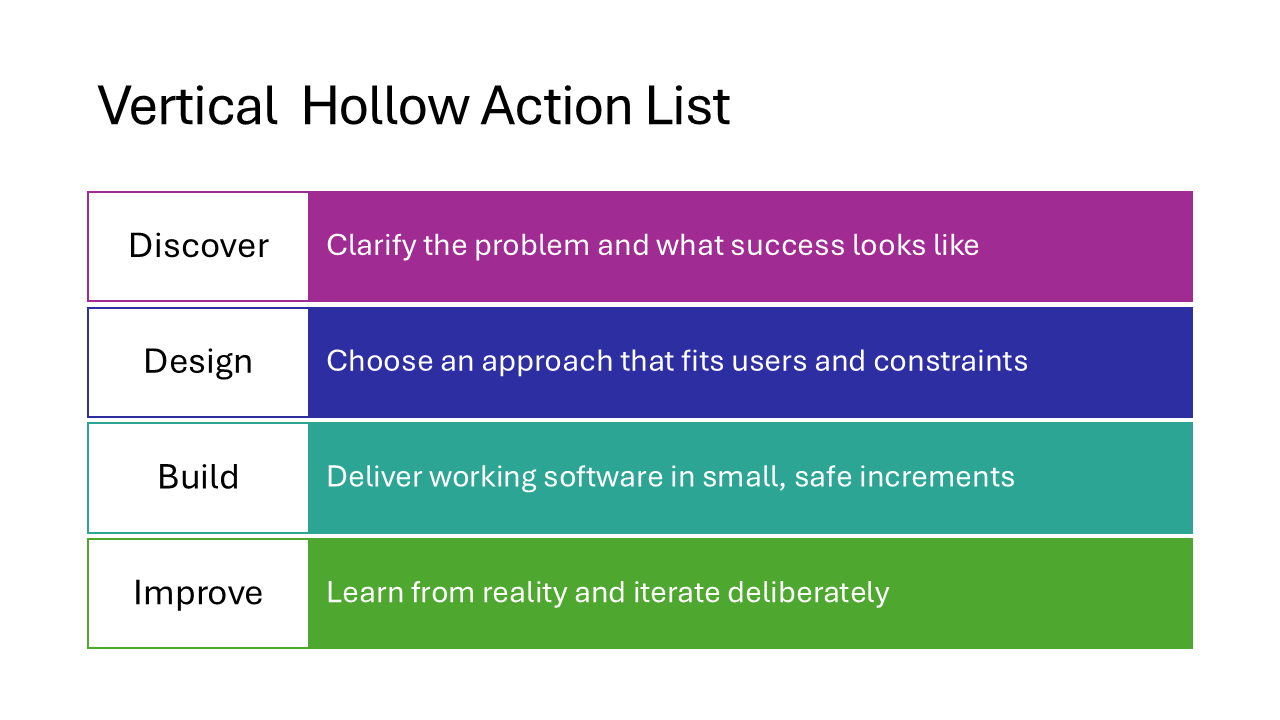

Vertical Hollow Action List

The outlined counterpart of the Vertical Solid Action List. Instead of filled bars, each item sits inside a bordered rectangle. The lighter look leaves more breathing room on the slide and works better on slides that already have a colored background.

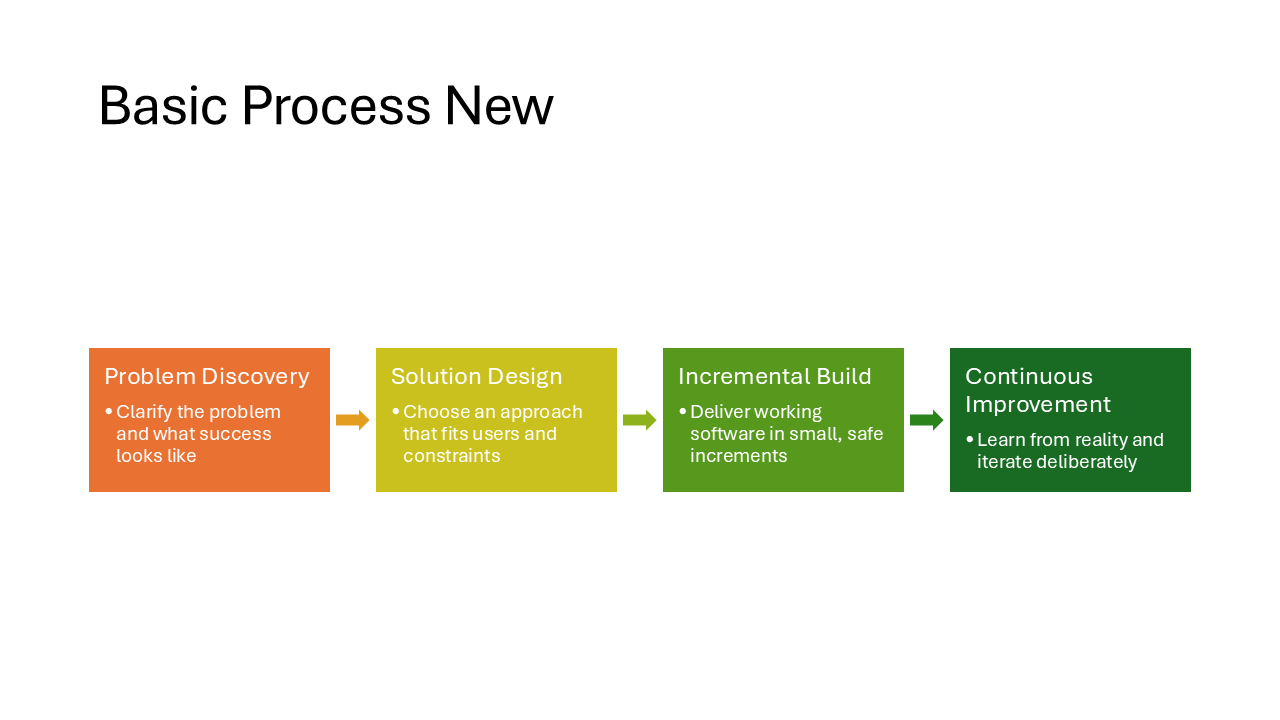

Basic Process New

A minimal left-to-right process flow. Each step is a colored rectangle connected by arrows, without numbering or extra decoration. Clean enough for a simple three-step workflow or onboarding flow.

Note

This one is only slightly different from the Basic Process layout that is available in the desktop SmartArt menu, but it has square corners and smaller arrows.

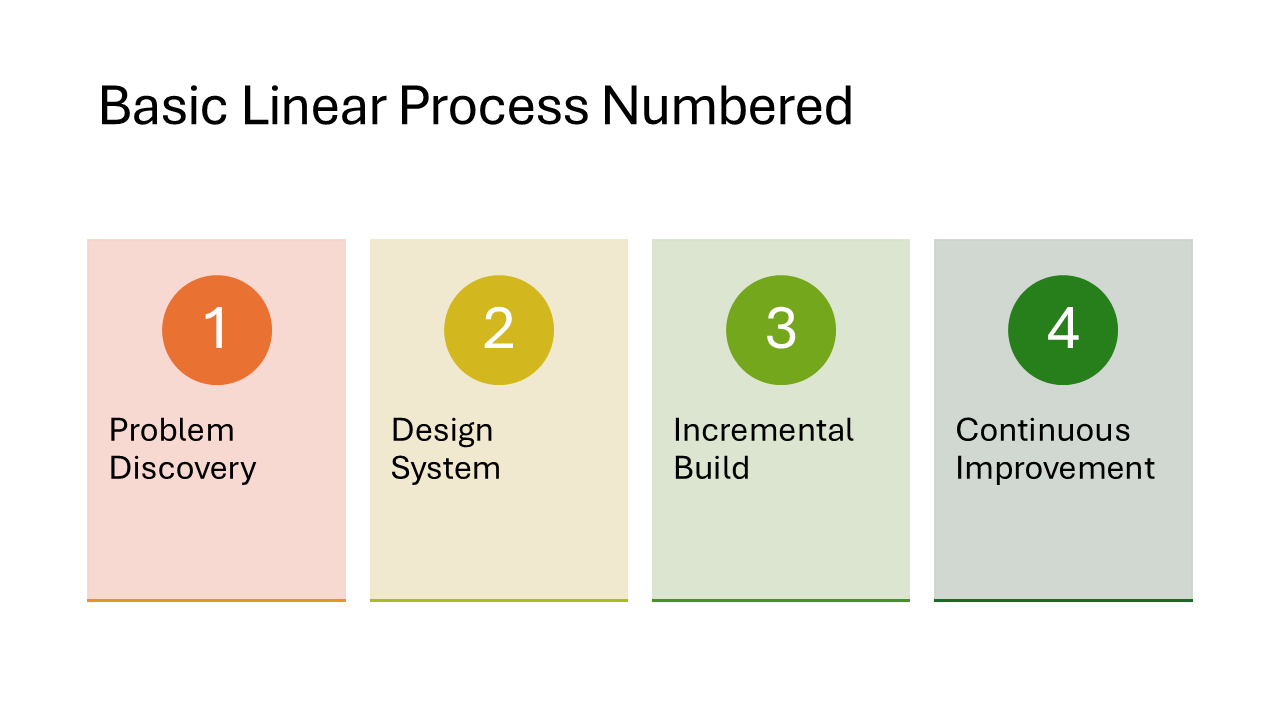

Basic Linear Process Numbered

Each step gets a large auto-generated number alongside a heading and description. The steps flow left to right in rectangular blocks connected by arrows. Useful when the sequence order of your steps matters and you want readers to follow 1-2-3.

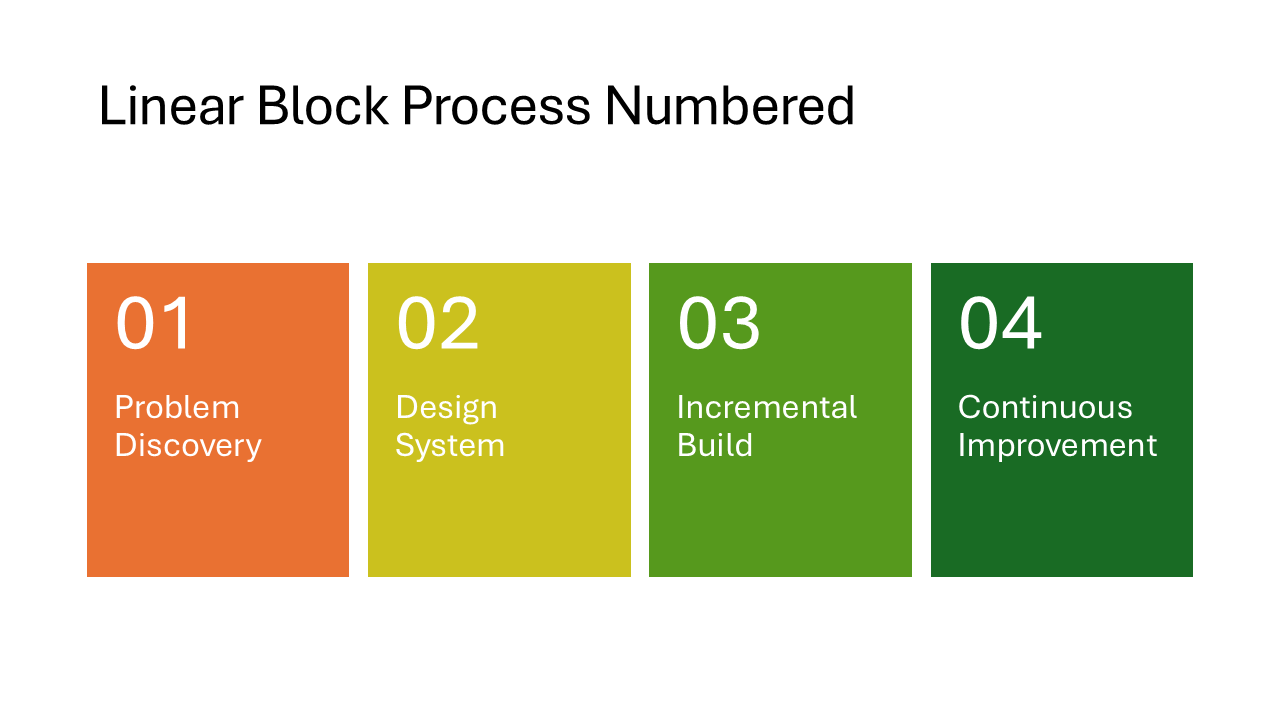

Linear Block Process Numbered

Similar to the Basic Linear Process Numbered but with thicker, blockier shapes that fill more of the slide. The heavier visual style draws more attention and works well when the process is the main message of the slide.

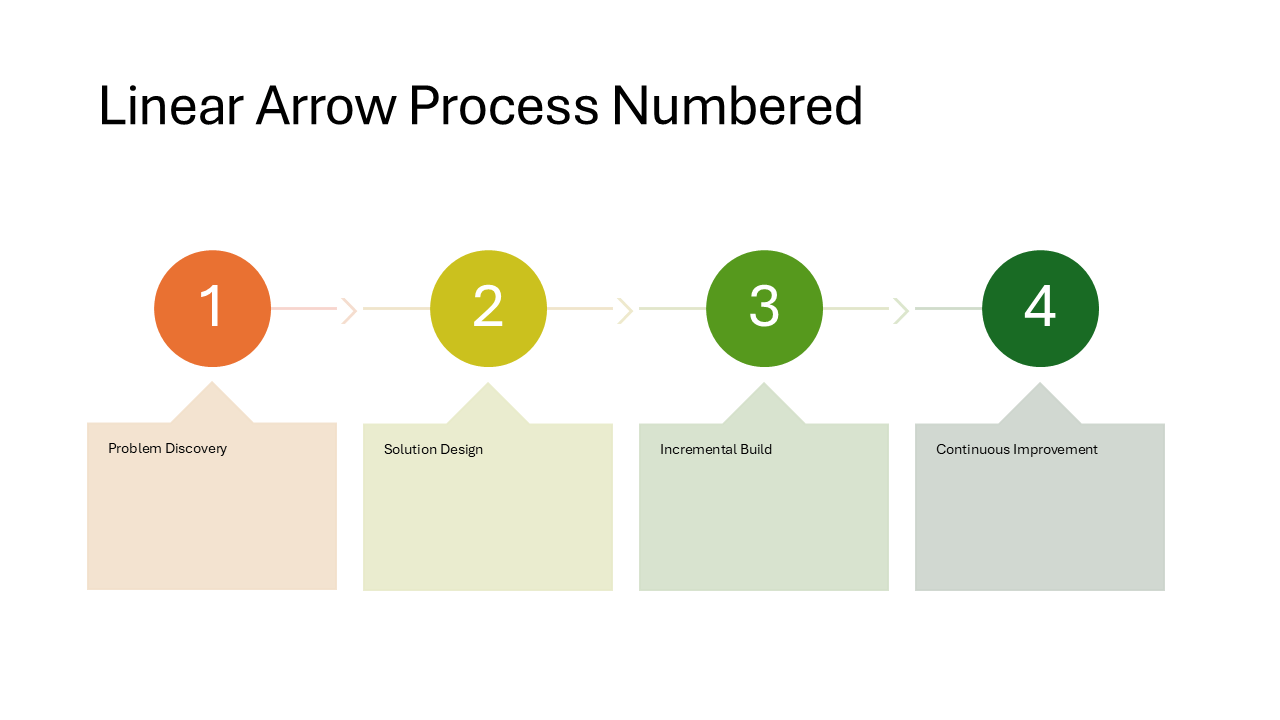

Linear Arrow Process Numbered

Numbered steps connected by prominent arrows, with text appearing in callout-style shapes that pop out from the flow line. Each step stands out more than in the block variants, making this a good fit for presentations where you walk through each step one at a time.

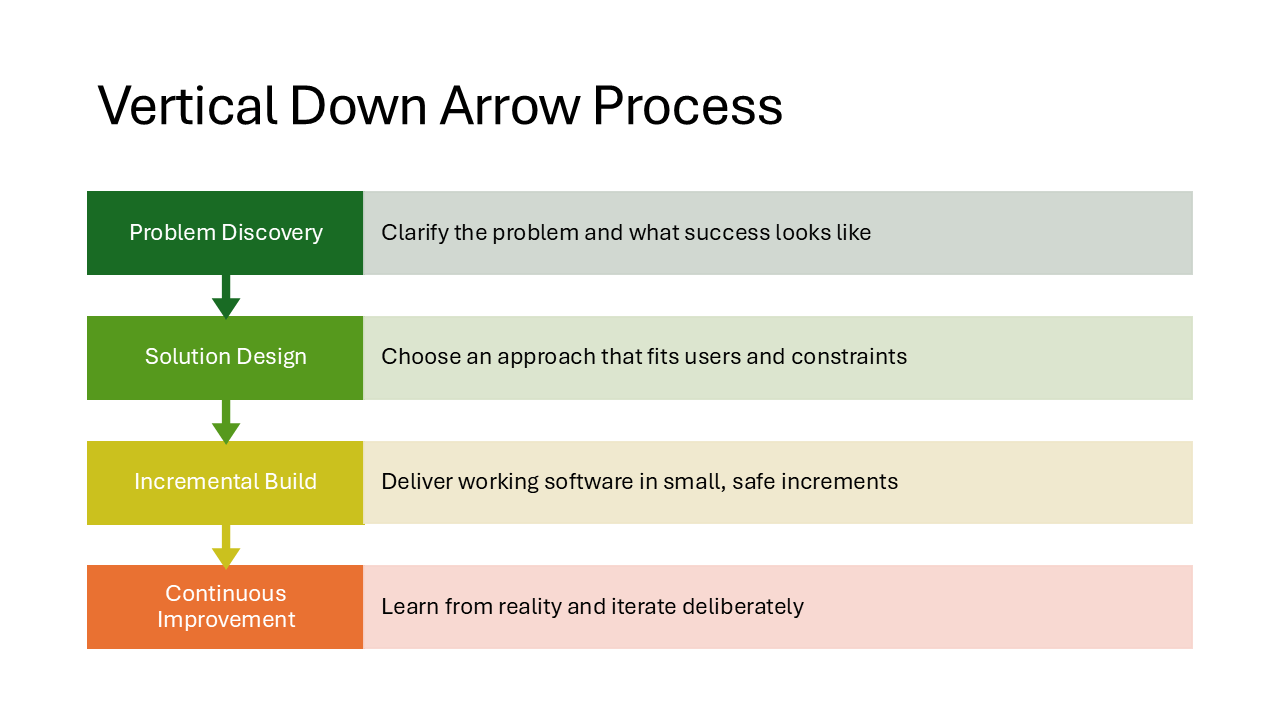

Vertical Down Arrow Process

Steps flow from top to bottom instead of left to right. Each step is a downward-pointing arrow with the heading inside and a description beside it. Natural for content that involves drilling down, filtering, or funneling.

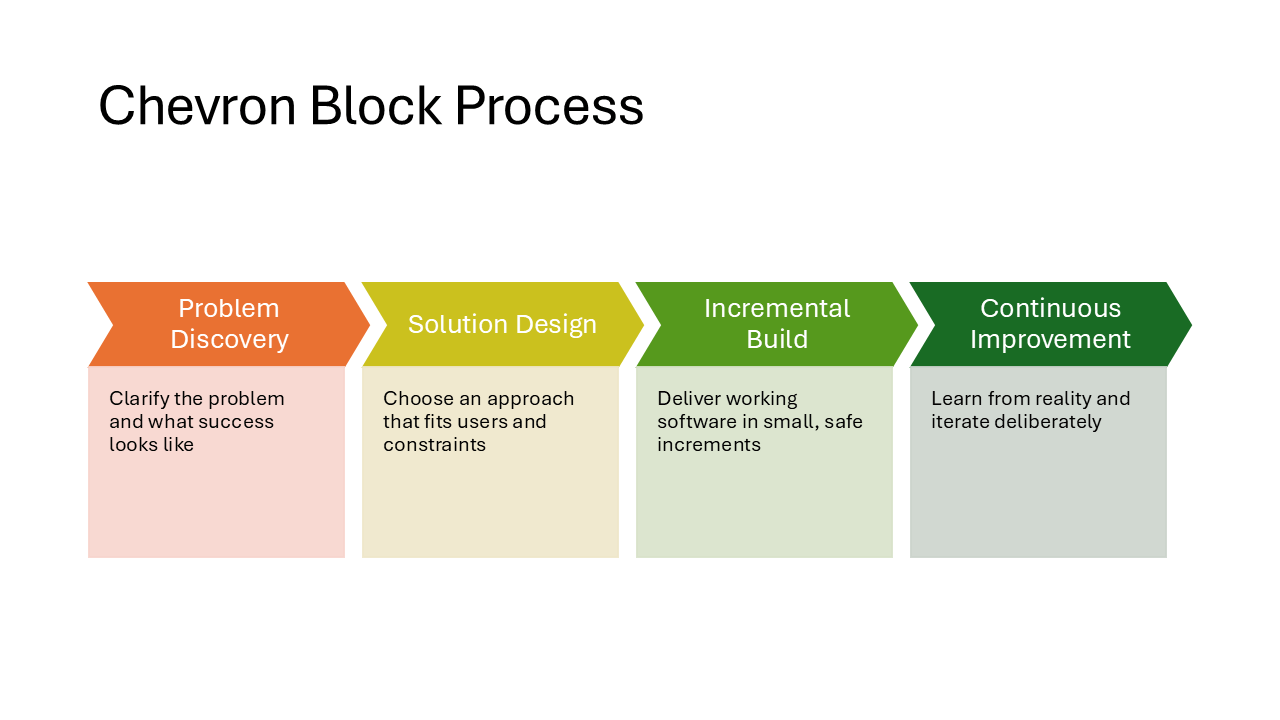

Chevron Block Process

Chevron-shaped arrows carry the heading text while rectangular blocks above them hold the descriptions. The chevrons create a strong visual flow from left to right. A solid choice for roadmaps or phase-based plans.

Layouts available in the web SmartArt menu

The following 8 layouts do appear in the web app’s SmartArt menu, but only when you use PowerPoint for the web. On the desktop they are still hidden and can only surface through Designer suggestions. If you primarily work in the desktop app, these are just as invisible as the group above.

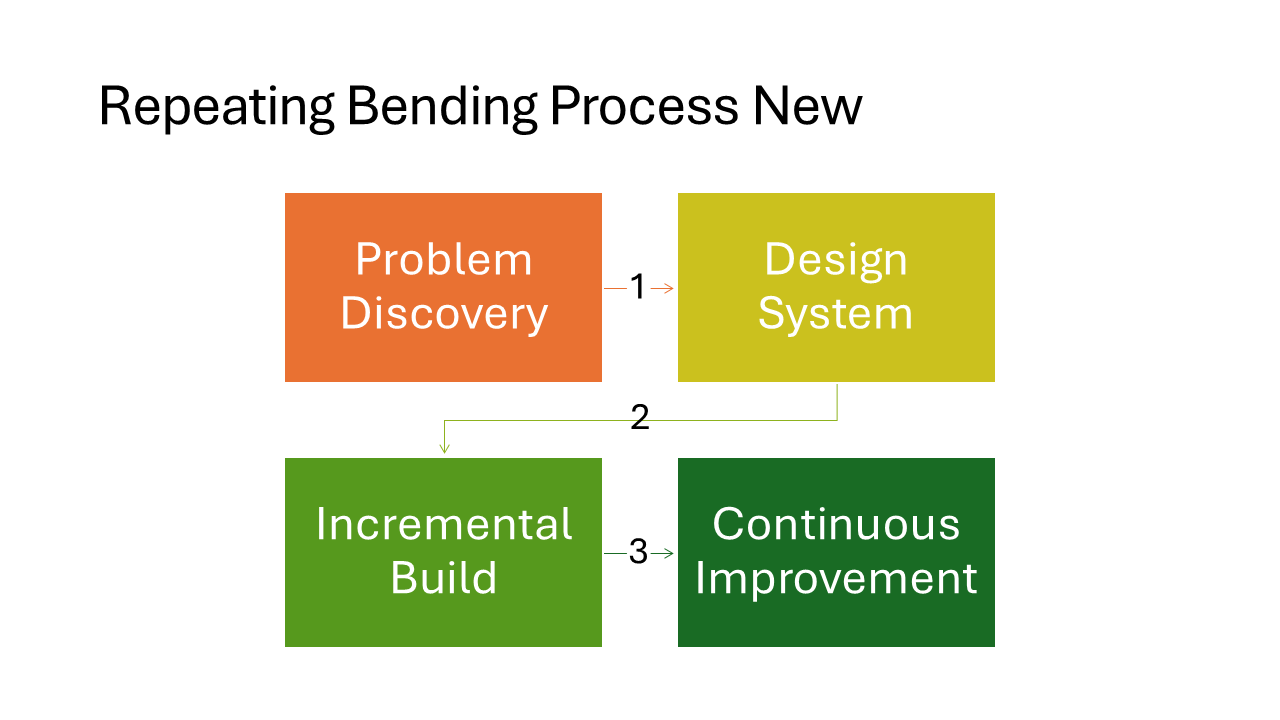

Repeating Bending Process New

A zigzag flow that bends back and forth across the slide. Instead of running off the right edge, steps wrap to the next row. Well suited for longer processes with six or more steps that need to fit on a single slide.

Note

In my experience, this layout is a bit buggy if you alter it in PowerPoint. The numbers on the arrows do not update correctly when you add or remove steps.

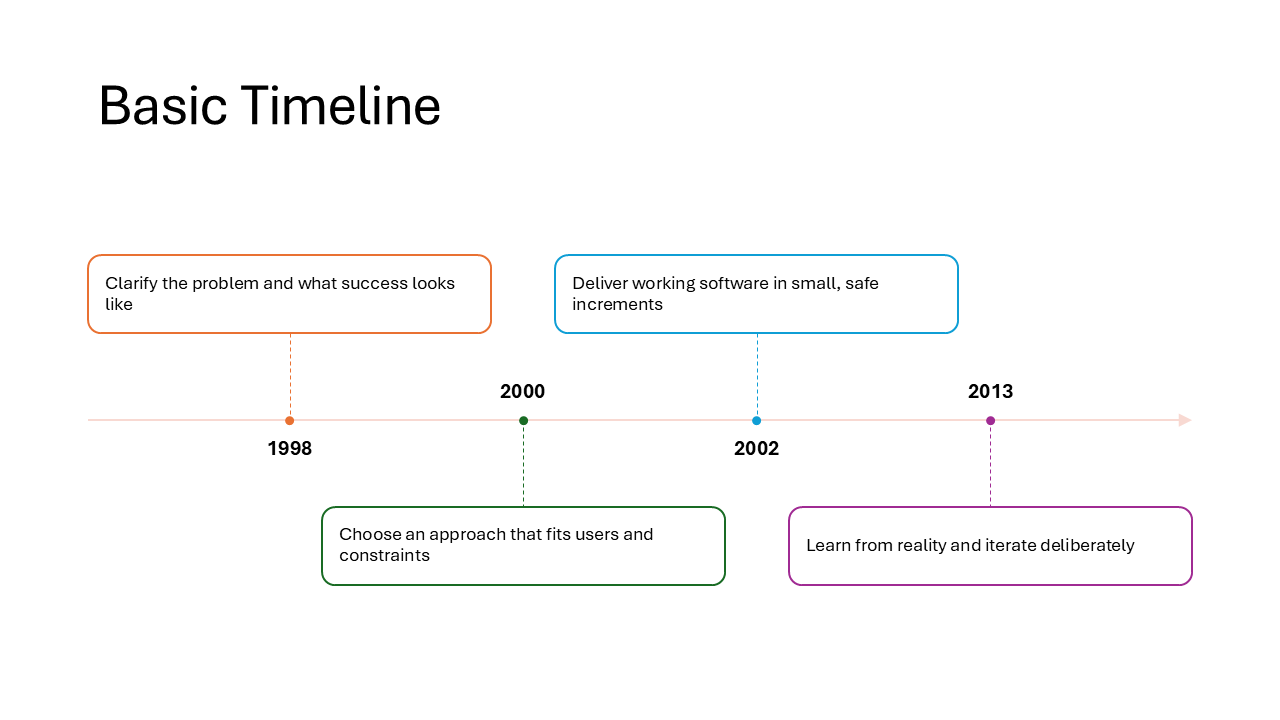

Basic Timeline

A horizontal timeline line with rounded rectangles for event descriptions and dates placed below. Straightforward and easy to read, good for project milestones or a brief history overview with up to five or six events.

Horizontal Path Timeline

Events sit in rectangles connected by a dotted path with circular markers at each stop. The path gives it a journey or roadmap feel, making it a natural fit for product release timelines or travel itineraries.

Horizontal Labels Timeline

Dates and labels sit directly above or below a horizontal line, without separate description boxes. The compact design keeps the slide clean and works best when each event only needs a short label, like version numbers or quarter names.

Drop Pin Timeline

Each event is marked with a map-pin shape, giving the timeline a location-themed look. The date appears near the pin head and the description below. A playful option that works well for travel recaps, office openings, or any content with a geographic angle.

Rounded Rectangle Timeline

Dates are the focal point here, displayed inside large rounded rectangles along the timeline. Descriptions sit beside or below them in plain text. Choose this when the dates themselves are the main message, such as deadlines or key decision moments.

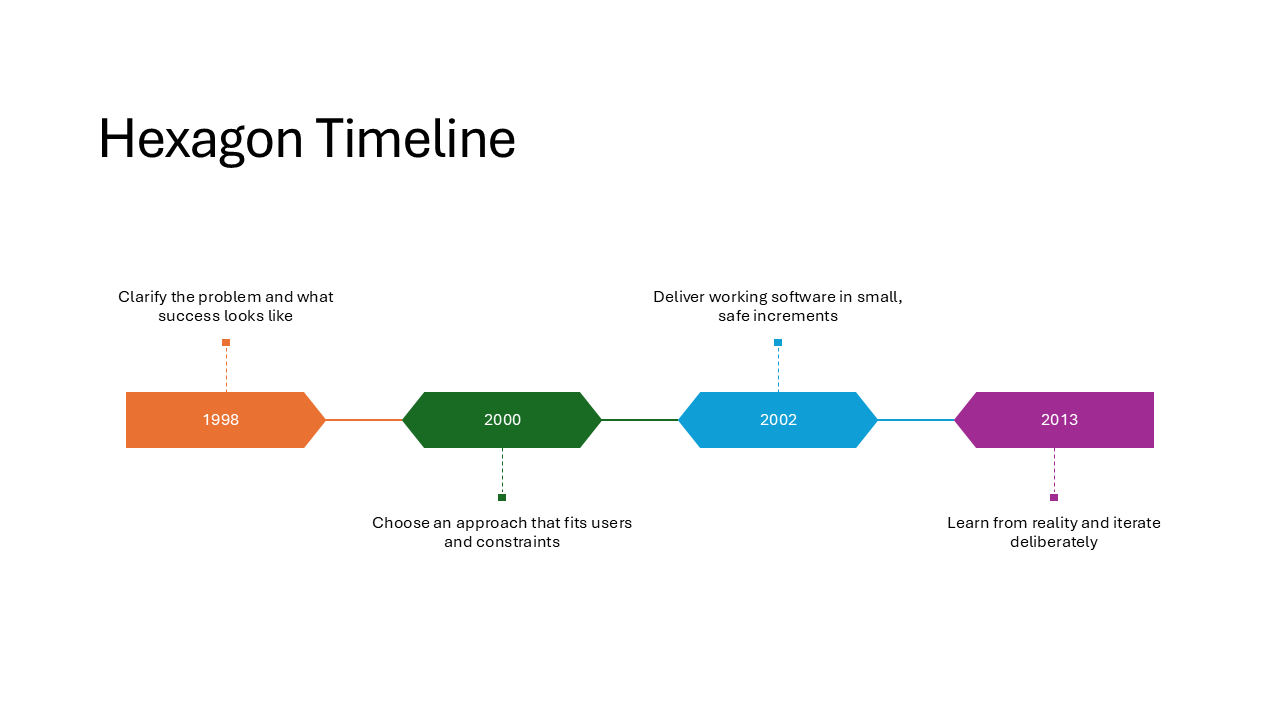

Hexagon Timeline

Similar to the Rounded Rectangle Timeline, but dates sit inside hexagonal shapes. The angular geometry gives the slide a more technical, eye-catching look. A good match for engineering milestones or sprint-based planning.

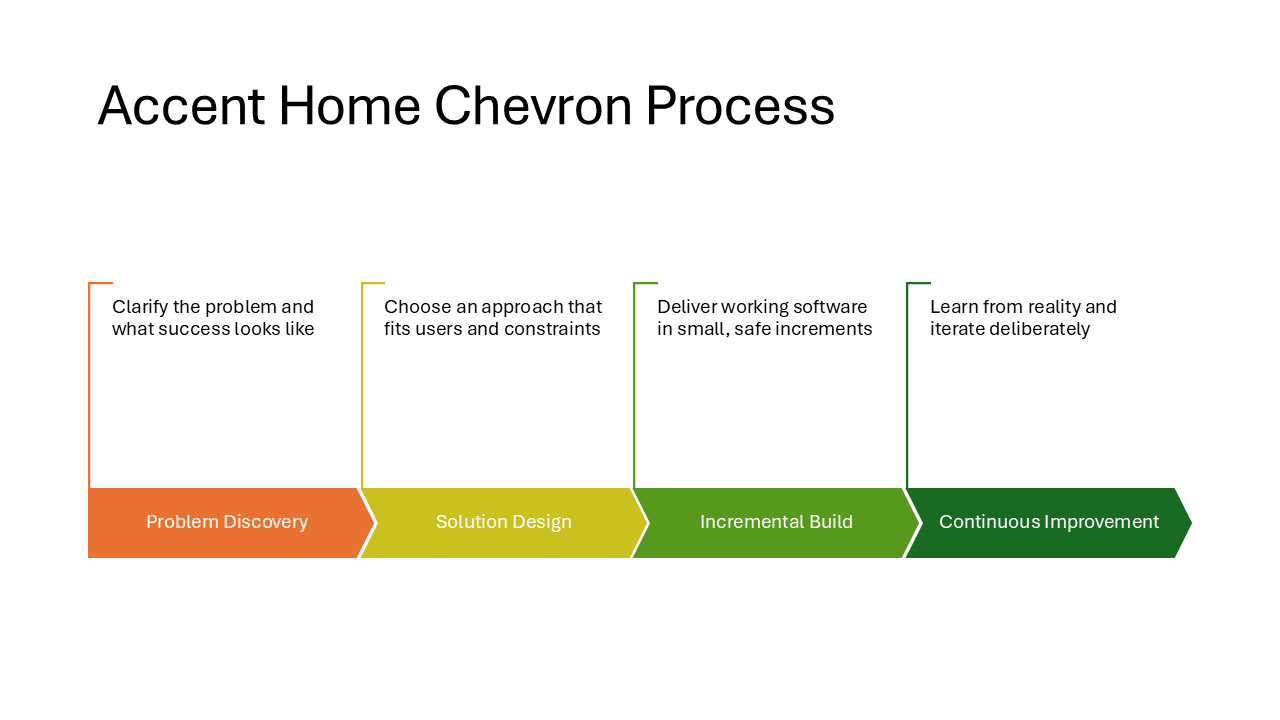

Accent Home Chevron Process

Chevron and home-plate-shaped accents carry the headings, with description boxes placed above them. More decorative than the Chevron Block Process and a good fit when you want a process diagram that also catches the eye in a print-out or PDF export.

Note

Although this layout has “Process” in the name, it is found in the timeline section of the web SmartArt menu.

Layout URNs for technical reference

Each SmartArt layout is identified internally by a unique URN. If you open a

PPTX file in a ZIP editor, you can inspect the uniqueId attribute in the

diagram XML to confirm which layout is on a slide. This is useful if you find a

new hidden layout and want to verify whether it already appears in the list

above.

Show layout URNs

All URNs share the common prefix urn:microsoft.com/office/officeart/. The table below shows only the version and layout name suffix.

| Title | uniqueId suffix |

|---|---|

| Icon Label List | 2018/2/layout/IconLabelList |

| Icon Circle List | 2018/2/layout/IconCircleList |

| Icon Circle Label List | 2018/5/layout/IconCircleLabelList |

| Icon Leaf Label List | 2018/5/layout/IconLeafLabelList |

| Icon Label Description List | 2018/2/layout/IconLabelDescriptionList |

| Centered Icon Label Description List | 2018/5/layout/CenteredIconLabelDescriptionList |

| Icon Vertical Solid List | 2018/2/layout/IconVerticalSolidList |

| Vertical Solid Action List | 2016/7/layout/VerticalSolidActionList |

| Vertical Hollow Action List | 2016/7/layout/VerticalHollowActionList |

| Basic Process New | 2016/7/layout/BasicProcessNew |

| Basic Linear Process Numbered | 2016/7/layout/BasicLinearProcessNumbered |

| Linear Block Process Numbered | 2016/7/layout/LinearBlockProcessNumbered |

| Linear Arrow Process Numbered | 2016/7/layout/LinearArrowProcessNumbered |

| Vertical Down Arrow Process | 2016/7/layout/VerticalDownArrowProcess |

| Chevron Block Process | 2016/7/layout/ChevronBlockProcess |

| Repeating Bending Process New | 2016/7/layout/RepeatingBendingProcessNew |

| Basic Timeline | 2016/7/layout/BasicTimeline |

| Horizontal Path Timeline | 2017/3/layout/HorizontalPathTimeline |

| Horizontal Labels Timeline | 2017/3/layout/HorizontalLabelsTimeline |

| Drop Pin Timeline | 2017/3/layout/DropPinTimeline |

| Rounded Rectangle Timeline | 2016/7/layout/RoundedRectangleTimeline |

| Hexagon Timeline | 2016/7/layout/HexagonTimeline |

| Accent Home Chevron Process | 2016/7/layout/AccentHomeChevronProcess |

Grab the PPTX and use these layouts in your own slides

I put together a PowerPoint file that contains every hidden layout listed above, pre-filled with placeholder content. You can download it, open the slide you need, and copy the diagram straight into your own presentation.

Download the PPTX with all hidden SmartArt layouts

Because these diagrams are regular SmartArt once they are on a slide, you can edit the text, change colors, and resize them just like any other SmartArt graphic.

Help me discover more

I am fairly sure I have not found all of them yet. Designer suggestions can vary based on your content, the number of bullet points, and possibly even your region or subscription tier.

If you come across a layout that is not in my list, I would love to hear about it.

Drop me a message and I will add it to this post.

Happy diagramming!